Dale Medearis is a senior environmental planner at the Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) ̶ an area government council. Medearis holds a Masters of Government Administration, an M.S. in cartographic and geographic science, and a Ph.D. in environmental design and planning. He spearheads the NVRC’s climate and international partnerships, using an international business model that is premised on the unilateral transfer and application of policy and technical innovations from abroad to benefit local communities. ESAL interviewed Medearis about how the partnerships are created.

DR: Could you tell me how the Commission supports regional governance?

Medearis: The NVRC is a political subdivision of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Our board is made up of the 13 local governments of the region: towns such as Leesburg to counties such as Fairfax. The NVRC is a mechanism to promote regional coordination, information sharing, and technical assistance for its members. Our 25-member board are representatives of the town and city councils, plus county commissions. I work for the NVRC’s small secretariat.

DR: How do technical innovations from overseas support community goals in the region?

Dale Medearis

Medearis: During about 20 years at the Office of International Affairs of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, I observed that the majority of international science and technology work consisted of basic research oriented toward national issues. Success in international science and technology cooperation was too often defined by signing ceremonies of agreements and, perhaps, a publishable paper, rather than outcomes of drinking water, renewable energy, or soil remediation programs in U.S. cities such as Flint, Cleveland, or Miami.

When I started in 2007 at the NVRC, I wanted to frame international collaboration around solving problems at the local level – town, city, or county – in Northern Virginia. Our business model is based solely around the transfer and application of policy and technical innovations from abroad to the localities of our region.

DR: Is the international collaboration model relevant to how we handle the COVID-19 pandemic?

Medearis: Indeed, the pandemic crisis has demonstrated our need for deeper global science-technology collaboration. When our local governments expressed interest in learning more about maintaining schools and businesses while physical distancing, we looked across the Atlantic to Germany, given their positive precedents in managing the pandemic. We organized a webinar between our board, Mayor Kämpfer of Kiel, Germany, and staff from the Stuttgart Regional Planning Authority.

We learned about the data and metrics that the German cities and counties were using to inform safe opening of businesses and schools. They shared specific benchmarks – numbers of people per square meter allowed inside – as well as health trends related to testing, infections, and mortality.

DR: Is it fair to say that the NVRC plays an advisory rather than an implementation role?

Medearis: Exactly, we convene elected officials, staff, and regional partners around policy needs and recommend creative problem-solving solutions for Northern Virginia. We find ways through our convening authorities to apply things in this region that have worked well abroad.

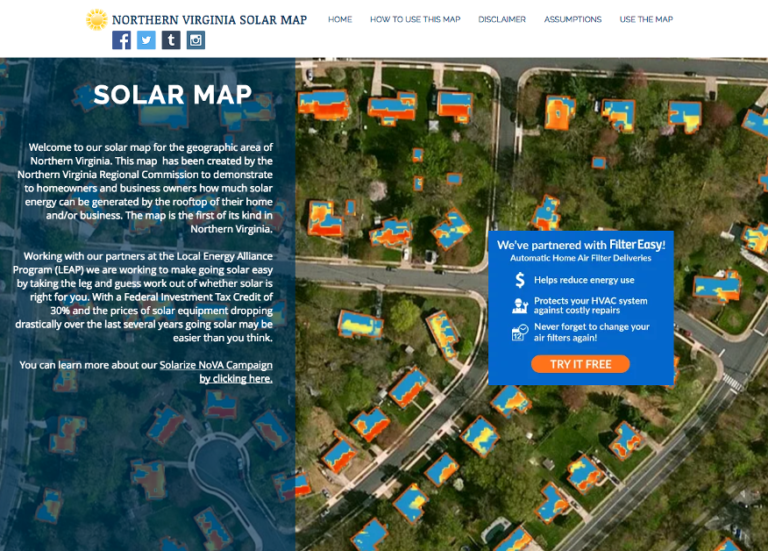

A great example would be the Solarize NoVA program. We studied how regions in Germany were mapping and deploying commercial and residential solar – especially the Stuttgart Climate Atlas and the Innovation City program in Bottrop. We liked what we saw and sought George Mason University as a partner. Between Professor Matt Rice and his team’s computing capacities and our land use, housing, and other data sets, we produced interactive solar maps for Northern Virginia. Today, homeowners can go to the Solarize NoVA website and click on the map, find their homes, and assess approximate costs, performance, and return-on-investment of rooftop solar PV systems.

DR: How do you gather the information you need about successful practices in other countries?

Medearis: We actually rely on a variety of methods to find, understand, and apply the policy and technology lessons from abroad to Northern Virginia. These include everything from developing case studies to conferences and workshops and international peer-to-peer study tours. All of these activities are in a problem-focused and goal-oriented context so that we stay strategically focused on outcomes. For example, the Arlington County Community Energy Plan was a product of a two-year series of peer-to-peer exchanges, studies, and evaluations about how to develop an operational climate mitigation plan. We sent Arlington elected officials to Germany, then engaged in follow-up workshops, resulting in a DOE grant.

DR: You’ve mentioned Germany several times as a place to look for innovative solutions to environmental and economic challenges. Why Germany?

Medearis: NVRC prioritizes its work abroad through two filters: does the county offer our region policy and technical innovations that will improve our environment, economy, and communities, and is that country invested in our region? By both benchmarks, Germany is an ideal partner. In the realm of energy, water use, waste recycling, food waste mitigation, and many sustainability indicators, Germany is a global pioneer.

DR: Where else has the NVRC engaged?

Medearis: NVRC has looked to Copenhagen, Denmark and Guelph, Ontario, for energy and climate innovations to aid with the development of the climate plans in Loudoun and Arlington counties. NVRC has also looked to the Dutch for lessons about climate resilience and adaptation.

DR: How do you make sure international outreach adds value to local organizations?

Medearis: Local authorities typically work with international entities in an event-based manner, which is important but not systematic enough to support long-term outcomes. We create problem-focused and goal-oriented contexts into which we string events, support them with analyses, and continually assess how to best support adoption of an innovation. Transferring any technology from abroad requires an orchestrated cooperation of the relevant actors – local government staff, universities and other research institutions, and international partners.

DR: What are some of the other U.S. partners that have played a role in these technology transfers?

Medearis: The American Geophysical Union is a fabulous example. The Thriving Earth Exchange program takes their members with science and technical backgrounds and makes them available to support local sustainability programs. A community partner, such as an NGO, a city, or even NVRC, can help facilitate the match of technical and science expertise to a specific issue. Right now, four AGU members at George Mason University are working on stormwater modeling, and we plan to connect them with faculty from the University of Stuttgart with expertise in green infrastructure.

DR: How does your technical background equip you for this body of work?

Medearis: I don’t really characterize myself as technical. Despite my second masters in cartographic science, I am a generalist who likes to work at the 30,000-foot level of policy development. My current work was inspired by my former work at EPA, as well as experience in Germany, where I was exposed to amazing projects involving green infrastructure and adaptive reuse of old industrial buildings.

I’m uncomfortable with the notion of “American Exceptionalism” and my work tends to reflect that. I think that we have an obligation to listen to and learn from the world – and demonstrate the value of that learning at the local level. International work is under-appreciated because people see too few outcomes that touch their lives directly. I aspire to try to change that.

DR: Do you feel that the work you are doing is helping highlight the value of adopting best practices from abroad?

Medearis: Certainly. We are bringing benefits back to the American taxpayer of engaging in international science and technology collaborations. It harkens back to the era of the late 19th century and the transfers of lessons from Europe to the United States. Daniel Gilman looked to Berlin and Freiburg when establishing Johns Hopkins University. Gifford Pinchot started the US Forest service by taking lessons from France and Germany. Stephen Mather’s work to create the US National Park Service drew inspiration from the Swiss.

DR: What would you recommend to scientists or engineers interested in international technology and policy transfer?

Medearis: People in the science, technical, or engineering communities aspiring to work internationally might consider kick-starting, or advancing, their careers with a focus on innovations that might be transferred to the local level in the U.S. I’d look for strategic international programs at places such as the American Society of Civil Engineers or American Chemical Society.

DR: Do you see change on the horizon in terms of how local governments benefit from technology transfer?

Medearis: Yes, I am banking on a paradigm shift within 10-15 years in the way our local authorities work globally – and hoping to see jobs that connect regional organizations, universities, and others with successful international models of practice!

Do you have a story to tell about your own local engagement or of someone you know? Please submit your idea here , and we will help you develop and share your story for our series.