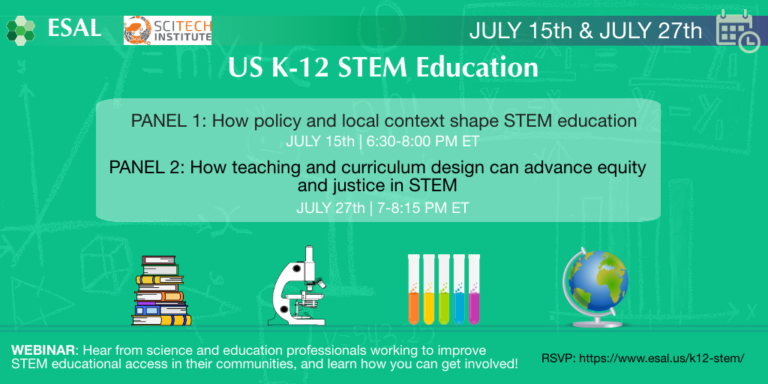

Science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education provides students with the tools to analyze, understand, and shape the world around them. However, due to accessibility, environment, or funding, not all students receive the empowering K-12 STEM instruction they need to thrive. To encourage discussion on this topic, ESAL hosted two virtual panel events with science and education professionals who work to improve STEM educational access in their communities. The first part of this series, called “How Policy and Local Context Shape STEM Education,” was held on July 15, 2021, and focused on how local funding, policies, and environmental factors impact students’ educational experiences.

The panelists featured four STEM education experts: Kayla Davis, Jeremy Babendure, Monica Taylor, and Andrés Henríquez, all of whom fight for STEM educational access in different parts of the country. For Oklahoma, Davis leads CodeSciLab to provide equitable access to STEM education through online programming resources and community outreach. Babendure, a native of Arizona, is the founder and executive director of the SciTech Institute, a non-profit organization that enhances community awareness and engagement in STEM through broad-reaching STEM initiatives. On the East Coast, Taylor educates elementary and high school students in Philadelphia on future careers in science and the healthcare industry while simultaneously serving as the vice chair on the Delaware County Council. Finally, Henríquez tackles STEM education access barriers in New York as the director of STEM education strategy at the global nonprofit, Education Development Center.

Each panelist brought a unique perspective to the conversation, first addressing the various barriers to STEM education access within state lines. The two main culprits, they all agreed, were school funding and limited access. Davis shed light on the budget cuts in Oklahoma that have restricted instructional hours and created a shortage of STEM teachers. Taylor cited the overall structure of public school funding as the problem for her state of Oklahoma, with disproportionate impacts in low-income areas. Babendure noted regional challenges to broadband access in rural Arizona communities, and Henríquez pointed out that in New York City, there are only about 20 minutes of science instruction per week.

When asked how to address these pitfalls of science education in our country, the panelists’ answers were vast. Babendure said he takes the approach of a “cultural hack,” attempting to change communities’ thoughts and opinions through science festivals and the SciTech Institute’s Chief Science Officers program. He also talked about increasing STEM role models in rural areas just by explaining to people that many of the jobs they hold are actually STEM-focused (e.g., dental assistants, mechanics), even though they may not realize it. Henríquez brought up his past experience working at the New York Hall of Science museum for his answer to the problem. “Learning science is not just in books,” explained Henríquez. From museums, to afterschool programs, to households, he says, “science education can actually be done in lots of different ways.”

Davis and Taylor both remarked on the importance of “exposure” for addressing the STEM education gap -- exposure to hands-on science at a young age, exposure to the plethora of scientific careers outside of engineering and medicine, and exposure to mentors who are STEM professionals with similar demographics are all important for the recruitment and retention of our future STEM workforce. “The more exposure that students have at the K-12 level, the more opportunities they have to go into science careers,” said Taylor. Programs like Early STEAM and the Health CareerX Academy in inner-city Philadelphia help to financially support underserved students who are interested in STEM. Davis tied in her personal experiences as a Native American woman in the biological sciences. “I have never met another Native American woman in-person who has a Ph.D. in my field; we are vastly underrepresented,” said Davis.

At the end of the event, all panelists were asked to give advice to people looking to get involved in STEM education. Taylor promoted the idea of working in local communities and thinking outside the box when creating afterschool programming. Henríquez advocated for volunteering at science museums or nonprofits like the 4H. Davis encouraged young advocates to get involved with efforts throughout the country or local community, and “get specific” if you start your own organization. Finally, Babendure offered a range of advice based on career stage. For example, he suggested that undergraduates may want to engage with high school students because of their near peer experiences, while industry leaders may consider inviting others to experience a “day in the life” of a STEM professional. To the attendees who are interested in policy, “start meeting your state legislatures and ask what their priorities are,” Babendure suggested. Legislators want to hear from their constituents, so this is a great way to find out what you can offer.

The bottom line? Get involved. Find ways to be a mentor, an advocate, or a role model, and learn how to make connections with policy leaders, community leaders, and government officials to shape STEM education in your local community.

For more information about how to get involved with STEM education in your own community, please see the links shared during this event and resources shared by the panelists. Part 2 of this series focused on how STEM curricula can be designed to promote equity and justice in the classroom and beyond, and will be covered in an upcoming article.

A recording of the webinar is available here .