Liz Snyder was elected in 2020 to the Alaska House of Representatives, winning by 11 votes to defeat Lance Pruitt. She comes to the House with a background in public health; her Ph.D. in soil and water sciences from the University of Florida complements her master’s in public health (MPH) from Emory University. As faculty at the University of Alaska Anchorage, preceding her election win, Snyder worked passionately to strengthen Alaska’s food systems. The co-editor Sowing Seeds in the City, she co-founded the Food, Enterprise, and Sustainability Hub of the North (FRESH). ESAL interviewed Snyder about her interest in community public health that has ultimately landed her in Alaska’s legislature.

DR: I am fascinated by your trajectory. When did you first become interested in public health?

Snyder: I grew up partly in Gainesville, Florida, but my family moved overseas for a handful of years, including to Pakistan. It made a big impression on me to see the challenges people face in other living conditions. Because my dad frequently talked about his work in air and water quality, I came to appreciate how people interact with their environments. It left me with vivid memories, as did Taiwan where we lived afterwards, and sparked my interest in public health.

DR: How did you hope to manifest that interest?

Snyder: I was always interested in environmental issues. It might have been naïve, but I thought that I could most productively work to manage our natural environment through a human health perspective. So, in college, I started doing healthcare work. I got involved with rehabilitation counseling – i.e., helping people with special needs figure out how to live independently. By the end of college, I realized that a healthcare setting wasn’t the best fit for me. I’m not sure anyone would want me as a rehab counselor, so I saved everyone some trouble!

DR: That’s when you shifted towards an environmental health approach?

Snyder: Yes, first I got my MPH, which just reinforced my interest in the interaction between natural and social sciences, such as human exposures to environmental contaminants in their communities. While mitigation and community response are important, I personally wanted to see more upstream prevention. A lot of contaminants that affect our health are in soil and water. So, the shift ended up being very intentional. I chose a Ph.D. program in soil and water sciences to get the training for proactive pollution prevention.

Liz Snyder.

DR: And then, I know you put your training to use as a professor in public health at the University of Alaska. How did that meet your goals?

Snyder: During my 12 years there, I sat on up to 10-15 thesis committees each year and advised more than 20. I covered a broad range of topics, not only water and sanitation, but also food security, healthcare access, health policy, and more recently COVID-19. My program was fully distance-delivered, which is not my favorite format, but worked well for my family. I loved the student interactions and teaching, and had the chance to pour my heart and soul into improving food security in Alaska. The Food Research, Enterprise, and Sustainability Hub that I co-founded with my colleague Rachael Miller at Alaska Pacific U. aims to improve circumpolar food systems towards sustainability and community ownership.

DR: With all the valuable work you catalyzed, why did you decide to run for office?

Snyder: I ran because our Alaska Representative just kept doing things I couldn’t agree with. And it turned out that running for office was actually a great path for me. During my campaign, I was contracted by the Anchorage municipality to conduct research on how the city should respond to the pandemic. Colleagues and I looked at nonpharmaceutical interventions around the globe as models, mapping how cases rose and fell. We considered the exacerbating effects of vulnerabilities such as homelessness and public transport. And our information was used at the state level, validating my run for office.

Snyder assists at a future community garden. Photo credit: Ari Wiggin.

DR: How did your Ph.D. help or hinder your effectiveness while running?

Snyder: When I ran the first time (and was defeated), I did not use “Dr.” in my title. The second time around, I decided to acknowledge the education I’d earned and the gravitas it conveys, and used my title. The result was my opponent accusing me of pretending to be a physician; I got labeled the “Dirt Doctor.” My credentials ultimately helped me win but I had to stay level-headed and not react to some of the criticism it bought.

DR: Has being in the Statehouse what you expected?

Snyder: In some ways I wasn’t surprised and felt well-equipped for the job. For example, after my 12 years of working in community health, I was used to working with people to find solutions to issues. Whether the issues are access to safe water, growing more food, or anything else, I am used to working with folks across the political spectrum and creating a shared vision to make change happen. So, that skill translated well to the political realm, and I am supported by a great staff.

Also, writing and trying to pass legislation is a lot like the academic process that I am familiar with. Basically, you identify a problem, research it, propose a solution, vet it with stakeholders, revise it, and defend it in committee and on the floor. It’s an awful lot like being a graduate student writing a thesis proposal and defending it to your committee.

DR: What aspects of your new position have been surprising?

Snyder: As a scientist you are accustomed to relying on the data to find solutions. If the data tell you something, you apply it to resolving the issue you’re working on. In contrast, in politics the data are not enough to generate the support you need to pass legislation, particularly in a legislature where you have a slim majority and it can be difficult to pass everything through. I had to learn to shop my legislative proposals around to my House colleagues and then go back to the drawing board.

DR: As someone trained in a data-based approach, has that been stressful?

Snyder: Sometimes, but I am well-suited for it. My aunt calls me “Switzerland” because of my desire to have the hard conversations across the aisle. While I’d consider myself both economically and socially progressive, I am comfortable talking with people who have contrasting points of view. I enjoy putting aside past disagreements to negotiate solutions because, frankly, that is how you get things done. Also, I am pleased to find that my work in office wraps back to my faculty work. For example, research data collected by my U. Alaska students is informing my development of legislation or amendments to other people’s legislation.

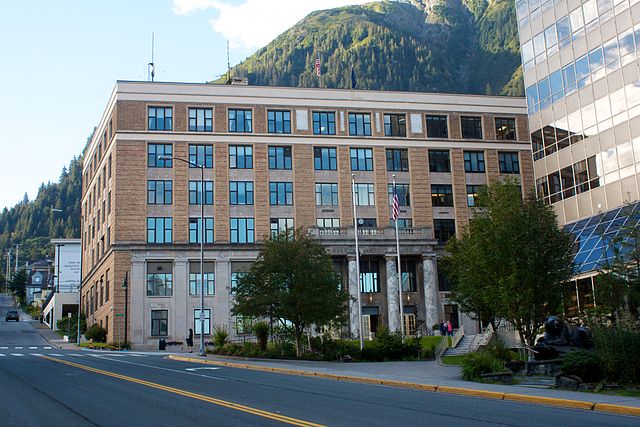

Alaska State Capitol Building. Photo credit: Jay Galvin

DR: What are some examples of legislation you’re working on?

Snyder: My first legislation was setting a deadline for the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services to get our public assistance applications available online. We are one of just a handful of states that don’t have this feature. The bill passed unanimously because I was able to cite the cost-savings and efficiency in processing online submissions.

Motivated by the pandemic, I also worked on changing our Alaska statutes regarding the job of pharmacist. As currently written, pharmacists, despite their roles in things like pain management and vaccinations, are not classified as health care providers covered by insurance. That legislation has not come to the floor yet.

And what I am most proud of is a bill to reduce wage-scarring, which is when you are stuck in a low salary as a result of a previous low-wage job. The legislation forbids employers from asking applicants about their past salaries or from retaliating against employees for discussing their salaries. And it requires that job ads include a salary range. This is a data driven policy, based on evidence that people are low-balled on their compensation based on their previous wage levels.

DR: That seems like an especially important bill as people are going back to work post-pandemic, many of them into different types of jobs.

Snyder: Exactly. And I subscribe to the idea of Health in All Policies – i.e., integrating health considerations into policymaking across sectors. Health is such a systemic concern, related to access to health care and healthy lifestyle choices. Whether people can afford it relates directly to where they are employed and what they earn. Many public health ills can be traced to whether we’re being compensated properly for the work we’re performing.

DR: How would you advise other scientists and engineers contemplating a run for public office?

Snyder: I’d support them, absolutely, because we need more people with science and engineering backgrounds in office. I’d suggest that they not question whether they are qualified or not, because many skills are transferable. That said, if you’re contemplating a campaign, you should reach out early to folks who can help you learn the ropes because trying to get elected requires a distinct skill set from being effective in office. There are local party offices and other organizations that can help you become a candidate. You can chat with local leaders to learn more about the political landscape and how you can play a role. Don’t wait for permission to run or for someone to ask you; just jump in!

Do you have a story to tell about your own local engagement or of someone you know? Please submit your idea here , and we will help you develop and share your story for our series.