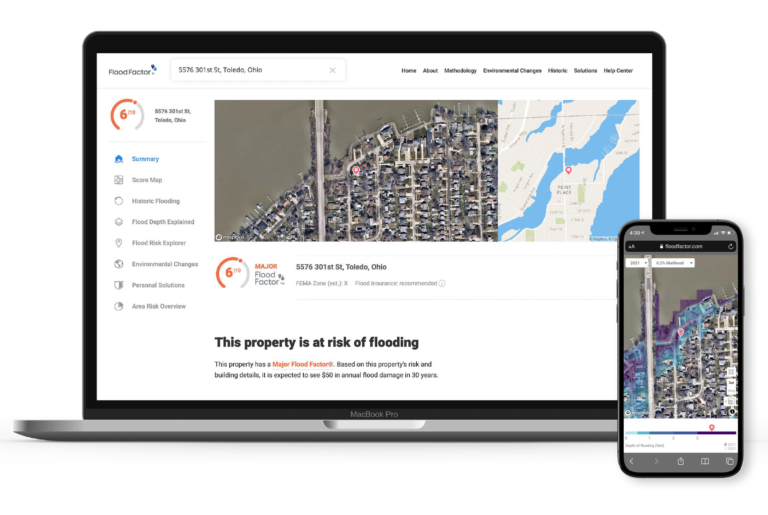

First Street Foundation is a Brooklyn-based nonprofit that uses data science to assess climate impact and to democratize that information for everyday people. First Street has developed a powerful web tool called Flood Factor to help homeowners across the US determine the flood risk of their property, down to the three-meter resolution. Anyone can go to floodfactor.com, enter in their address, and receive an immediate flood risk score on a scale of 1 to 10, projected out over the next 30 years. ESAL recently interviewed Ed Kearns, who holds a Ph.D. in oceanography and serves as chief data officer for First Street Foundation, to discuss the development of Flood Factor and how they think about climate change.

LZ: What is First Street Foundation and Flood Factor?

Kearns: The genesis of the Foundation was trying to inspire climate action. We are not a policy advocacy group -- we’re not saying do one action over the other -- but we want to make climate risk available for those decisions to get made. We want to democratize data for everybody, not just scientists or policymakers, by communicating all the way down to the individual American, and we understand that the complexity of the information is a significant hurdle to overcome.

To create Flood Factor, we’ve taken a lot of open source data -- NOAA precipitation records, hurricane tracks, USGS stream gauges, and topography -- and we’ve integrated them into a hydraulic model for flooding. What we are producing at the end are very simple products, so people can walk away with two numbers: the severity of their risk and what it could cost.

LZ: How does Flood Factor determine flood risk and flood damage?

Kearns: Under different climate scenarios, we can predict the amount of water that will stack up on the ground across the entire US. Our focus is quantifying today’s risk but also how that risk will evolve by predicting rainfall, storm surge, and sea level conditions through 2050. We do this projection on a property-by-property basis and even within a property that has a creek running through it, for example, we can predict where the water is going. From market research, we found that a 1 to 10 scale is a good metric. When you try to boil all the complex science down to one number, there are some challenges, but we think we've done a pretty good job.

So we can calculate the presence of water, but then it’s a matter of whether that water will cause damage. And that depends on how your house is situated. Is the water going to reach the property? If so, is it going to reach the house? We estimate the average annual loss and present the cost alongside the risk score.

Ed Kearns

LZ: How is Flood Factor able to achieve a level of granularity down to individual homes all over the country?

Kearns: We know the boundaries of every property. We know the footprints of every building. We have data partners that have provided parcel-level information, which are aggregated from county assessor records and other public sources. The two greatest determinants for damage are the building’s first floor elevation and whether there’s a basement. But when the data are incomplete, we have to use machine learning to make educated guesses.

LZ: What other considerations went into the development of Flood Factor?

Kearns: We launched Flood Factor back in June of 2020, but even before we launched, we were working with a number of groups including the National Association of Realtors. There were plenty of concerns voiced about the impact of making this information available in the real estate market. After the launch, though, those concerns faded because consumers are seeking out flood risk information and now we have integrations with real estate sites such realtor.com and redfin.com.

LZ: How has Flood Factor been received by the public so far?

Kearns: We are at over 3 million unique users already and over a quarter million of those were just in one day -- that one day was during Hurricane Ida. People were alarmed and wanted to know if First Street predicted their home to be at risk of flooding even though it was too late. It’s a heartrending story, but that’s the insidious thing about climate change. You may have lived in an area your entire life and never saw flooding before. Now you have these enormously damaging rainfalls that are turning into storms beyond our normal human experience. We're trying to translate the complexity of the models and get people to take a closer look.

Ed Kearns speaking at in a panel.

LZ: How will communities benefit from a tool like Flood Factor?

Kearns: The train has already left the station on things like heavy precipitation, so we have to learn to adapt. There is no national database of flood adaptation features. By and large, these are local state or county projects. We built a massive database of 23,000 features like levies, pumps, canals -- and we didn’t even get them all -- to take into account in our model.

One thing we’ve been trying to do is to make our data available to local communities. It has proven to be very difficult because there’s 3000 counties in the US and only 30 of us at First Street. How do we get this information into the hands of communities to help them start planning? When you make investments in infrastructure, one question is where do you spend that money for maximum effect? We are hoping that our data can be used as a screening tool to help direct engineering projects. We can be the ‘first cut’ to understand where a community might need to literally dig deeper and find out what they need to install to protect against flooding.

LZ: What’s next for First Street Foundation?

Kearns: We’re working our way down the list of climate perils. Right now, we’re computing wildfire risk. After that we have heat, convective storms, landslides, mudslides -- what they call billion-dollar climate disasters. Unfortunately, we have a lot of work to do.

LZ: Finally, what are your thoughts on local government and climate risk and adaptation?

Kearns: The COVID pandemic has laid bare a lot of the issues with our federal government. In the early days of the pandemic, local health officers were on their own to protect their communities. Disasters like flood and fire are at the same scale. They require local action but the resources aren’t there and there are all sorts of equity and justice problems baked in. We see it with the pandemic, and with flood and fire, where certain communities are more vulnerable than others. We have to figure out how to untangle this web and it's going to be done at the local level. It has to start there.

Are you involved with an organization or effort that you think might be of interest to the ESAL community? Or have heard about an organization or initiative that you’d like to learn more about? Let us know here, and we may feature it in a future post.