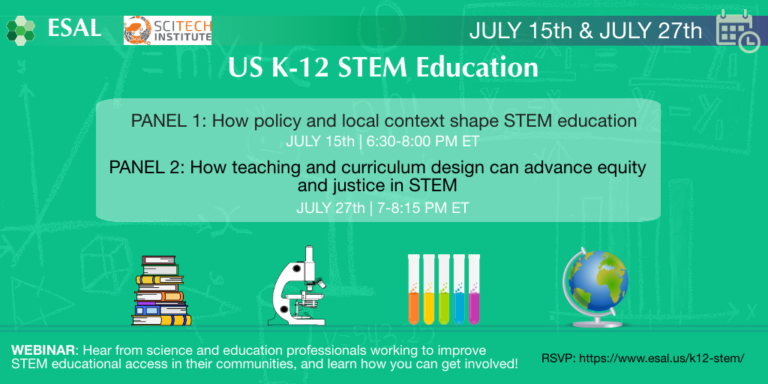

On July 27, I attended an ESAL panel on K-12 STEM education, the second of a two-part series, which focused on equity in teaching and curriculum design. The evening’s panel featured: Sam Long, a high school science teacher in Colorado and transmale activist for inclusive biology education; Rasheda Likely, an assistant professor of science education at Kennesaw State University who developed an after-school STEM program for Black girls; and Daniel Morales-Doyle, an assistant professor of science education at the University of Illinois, Chicago, whose experiences have bridged politics and science.

This event was one of the most powerful ones I’ve attended among ESAL’s virtual programming since COVID-19 hit. The speakers’ insights were refreshing given the past year of economic and racial turbulence, with excellent moderation by guest host Deepali Ravel, who serves as the director of education for the Harvard Infectious Disease Consortium. I was surprised by how affected I was by the speakers’ stories, provoking me to reflect on my own educational upbringing.

As an ESAL volunteer for the past two and half years, I’ve had the opportunity to interview scientists and local leaders and write about the impact of local government. Never did I stop to consider how I got to where I am -- a millennial, Chinese American, cisgender female, and chemical engineer by training. My father was an agricultural scientist whose own educational accomplishments enabled him to escape communist China and pursue a freer, more meritocratic life in the U.S.

In college, I joined the minority of women that pursue engineering (only about one in five bachelor degrees in engineering went to women in 2017-2018). My Asianness, though, was the shield that exempted me from being an outsider. Seeing other Asian students, professors, and colleagues in STEM reinforced that I belonged. The visible connection between my identity and the faces of STEM provided me with a sense of security and comfort, and filled a subconscious need for belonging.

How much of my path was driven by the archetypal image of an engineer based on people who look like me and how much of it was my own propensity for science and math? The truth is a complex mixture of both. To do the thought experiment of removing social and familial influences from my experience, or anyone’s, is nearly impossible.

One can try to imagine the challenges facing a Black woman in STEM, such as Likely, who was not living up to an expectation but, instead, defying it. During the event, she shared an anecdote of how girls in her Black-centric “Science through Hair Care” program laughed in her face when she told them that she was a scientist. She was not the white male paragon they envisioned. As a teacher-educator preparing the next cohort of science teachers, Likely wants to push back against the tokenization that minorities often feel in STEM. She hopes science education can evolve into a celebratory and caring space, and ultimately ensure that future generations of underrepresented individuals do not have to undergo the trauma of being “the only (blank)” in the room.

For Morales-Doyle, personal politics have always been intimately tied to his work -- first as a high school chemistry teacher in Chicago public schools and now as a teacher-educator. His formative years were spent watching his father, a community organizer, work to shut down two medical incinerators in their neighborhood. Those facilities not only posed dire health consequences, but also presented a problem that was both political and scientific in nature. Since then, Morales-Doyle has questioned the ideologies we absorb as part of the educational status quo. “To say science is nonpolitical is an escape route,” he explained. Morales-Doyle sees equitable and inclusive STEM education as a way to connect socio-economic issues that are relevant to everyday life.

The third panelist, Long, descended from generations of scientists. Similar to my own story, his parents immigrated from China to pursue a better life. But his story diverged and became even more compelling as he shared his journey of coming out as transgender and later falling into his profession as a high school biology teacher. Long has now come full circle as the cofounder of genderinclusivebiology.com, a resource for teaching the biological spectrum of sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Together with two other gender-identified teachers, Long is changing how biology is taught by moving beyond the binary model of man vs. woman, or XY vs. XX chromosomes. Instead of pathologizing variations, they are normalizing them.

Although the struggle for equity in STEM continues, the panelists showed a relentless desire for change. Long, Morales-Doyle, and Likely amplified each other’s energy and had these final lessons to teach us:

This event was co-hosted with the SciTech Institute in Arizona. For more information on inclusivity in biology education, visit http://www.genderinclusivebiology.com. For more information about how to get involved with STEM education in your own community, please see the links and resources shared during this event. Part 1 of ESAL's series on K-12 STEM education focused on how local policy shapes STEM education.