The Children’s Environmental Literacy Foundation (CELF) is a not-for-profit that helps K-12 students explore real-world environmental problems using sustainability as a guiding framework. CELF’s Civic Science Program, for example, illustrates the organization’s commitment to place- and project-based learning. This program has engaged students throughout the Lower Hudson Valley, New York City, Los Angeles, and soon Houston, in collecting and synthesizing environmental data, learning implications for human and ecosystem health, and developing advocacy skills through formal presentations to local councilpersons and decision-makers. Founder and Executive Director Katie Ginsberg, Director of Education Victoria Garufi, and Educator and Professional Development Facilitator Lisa Mechaley spoke to ESAL about CELF’s history, mission, and successes.

CK: How did CELF come together?

Katie Ginsberg, Founder and Executive Director

Ginsberg: Although I am not a formal educator by profession, I was in the marketing and advertising field and worked on a number of consumer product campaigns. Throughout that period in my professional life, I learned a lot about the research and development behind consumer products. That piqued my curiosity around some of the ingredients and raw materials that are used in consumer products, particularly personal care and food. It was the nascent beginnings of thinking about how things are made, what they're made with, and supply chain economics.

Fast forward to when I became a mom and had three children. At the time CELF was created, my oldest son was in fourth grade, and his experience in elementary school was very influential in my thinking about not only what we’re feeding our kids and putting on them - sunscreen, shampoo, etc. - but what and how they were learning. On Earth Day, my son came home extraordinarily excited and enthusiastic about how the school had transformed a typical day into this full-on experiential day with the students being asked to be environmental detectives. Their charge was to identify environmental hotspots or areas where there was waste or any garbage. They became empowered to, essentially, investigate the school and see where there were leaky faucets, where there was litter on the school grounds, where lights were on that perhaps didn't need to be, and so forth. He came home and quickly became our household environmental policeman. He was really keen to see our family do more personally to be environmental stewards. But Earth Day came and earth day went. Over the ensuing weeks there was less interest on his part.

This was an epiphany moment for me. I realized that these critically important issues around the environment were being addressed in infrequent, isolated ways. Schools, at that time, were using Earth Day as the one shot at discussing it, but it really wasn't seen as the powerful lens through which kids can learn and better understand the connection that we as human beings have with our environment, the natural world, and with each other. This turned into two years of research and exploration and a lot of conversations with educators and others in various fields like environmental law, environmental governance, and corporate social governance. Within 12 months I had an initial board of directors, filed, and was approved as a non-profit.

CK: How do you reach students?

Ginsberg: We decided that the most efficient way to reach as many students as possible would be to work with teachers because they are the people that our kids see five days a week, nearly 300 days a year. If one teacher has interest in using sustainability as a context for teaching, that one teacher has the capacity to reach anywhere between 20 and 150 kids every year. We focused on professional learning as the delivery mechanism to reach as many teachers as possible. We funded a first Summer Institute for nearly 40 teachers in 2005 with support from a New York State Special Legislative grants program and individual donations, and we worked with a local education partner to host the event. The Summer Institute became a flagship program for CELF and continues today. It’s a deeply immersive program for teachers and administrators to rethink the purpose of education. Why did they go into the profession in the first place? And how can they use sustainability as a context for engaging their students in these topics that matter to them, that help them understand long-term thinking and give them a greater sense of how things are connected in ways that conventional or traditional education systems have not.

By virtue of working with teachers and administrators as our primary audience, over 16 years, we have reached one million students. We're really proud of the ability to have the impact through these authentic professional development programs with teachers and in school communities. We’re not dependent upon downloadable lessons, but rather what we think of -- and what teachers give us feedback on -- as truly transformative educational experiences.

Lisa Mechaley, Educator and Professional Development Facilitator

CK: Tell me about the Civic Science Program? What kind of projects were undertaken in New York?

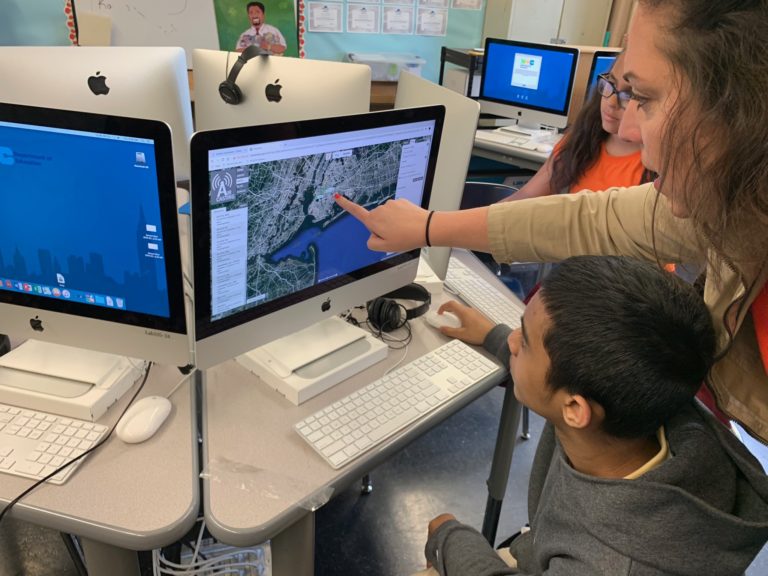

Mechaley: Beyond the education for sustainability, we’ve been working on our approach to our Civic Science Program, which unpacks our inquiry-to-action framework. The civic science program takes students through developing their inquiry questions, to data collection, to analysis, collaboration, innovation and action. It’s been in the making for two and a half years. The program was piloted and developed with a focus on air quality. It was funded by the New York State Pollution Prevention Institute, which is why we went in the direction of improving air quality in our school communities. Through the implementation, we’ve recognized the need for place- and project-based learning. This is a framework that can be applied beyond air quality, to water, soil, or biodiversity.

Ginsberg: We started this program in collaboration with the Mount Sinai Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit. For years, they have provided much needed environmental health resources for NYC residents. Through CELF’s partnership with the NYC Department of Education, Mount Sinai recognized the opportunity to partner with us on a program for NYC public schools using their health research and data related to air quality, particulate matter, and health issues such as asthma. The program uses an air-quality monitoring device called AirBeam that measures PM 2.5, which are very small carbon-based particles that pass through the alveoli into the circulatory system and lead to systemic health problems. Mount Sinai identified hot spots in specific communities in Harlem and the Bronx that have environmentally-induced asthma. This project was one way to help empower those students with data-driven knowledge and advocacy skills and also to begin to get a snapshot of air quality throughout New York City.

In Houston, we are going to pursue water quality, as well as air, because of the issues that are so relevant to them, such as extreme weather events. Hurricanes, flooding, and water quality problems are common everywhere, but they are particularly important in that region because they're faced with those issues on a regular basis. This speaks to CELF’s emphasis on place-based education -- how we adapt and modify what we do for local relevance.

CK: What is the importance of civic science?

Vicky Garufi, Director of Education

Garufi: I think that one of the biggest takeaways for us at CELF, and from what we've seen from the teachers, is that it's relevant. It's something tangible that they can do with their students. It has many STEM connections -- it’s engaging students in science, technology, data collection, and engineering. Students are coming up with solutions and innovations in their projects. We're actually doing a training workshop working with science and math teachers right now, and the teachers are going through data comparison and the statistics in a meaningful way. Some of these students have said, “We're not just reading other people's research, we're contributing to that research. We are collecting the data, we are out there in the field, these are our numbers.” And I think that's an important thing for the students. They're committed to this and they actually have agency in the project.

CK: What are the biggest opportunities for the Civic Science Program, and for CELF, going forward?

Garufi: We’re looking at how we can replicate this program and expand our reach. We've had three teacher cohorts that have gone through the training with us and we have refined it along the way. What we're looking to do now is to have an existing group of existing teachers in LA, who we worked with in another pilot program, do this remotely. We’re aiming to have these tools available online to do a series with virtual learning.

Please see CELF’s video on the Civic Science Program for more information.

Are you involved with an organization or effort that you think might be of interest to the ESAL community? Or have heard about an organization or initiative that you’d like to learn more about? Let us know here, and we may feature it in a future post.