Everyone knows it’s impossible to accomplish anything in scientific research without a tremendous amount of work. Yet in the traditional view, handed down through legends about great scientists of the past, science wasn’t work at all; rather it was a kind of inspired play that yielded the intellectual and perhaps spiritual rewards that can only come through original scientific discovery. Stories are told of Ernest Lawrence, the American Nobel laureate physicist, working in his lab around the clock, seven days a week. Lab workers were expected to put in 70-hour shifts, but many had fond memories of Lawrence dropping in to chat any hour of the day or night, intrigued by the challenges his young assistants were working on. No regular hours, no publication pressure, just a circle of brilliant minds working together to unlock nature’s deepest secrets. Paradise!

Compare that to contemporary science: a world of intense competitive pressures,strict hierarchical teams, and frequently all the difficulties and discontents that go along with working for a living anywhere: salary, benefits, job security, work-life balance, career advancement. Early career scientists, especially, say the old scientific training system, where you earned a PhD in graduate school, put in a few years as a postdoc in someone else’s lab, then eventually went on to run a lab of your own seems further and further out of reach. What happened?

To investigate these changes, ESAL hosted a discussion featuring four panelists, all of them differently positioned to observe the vast changes taking place in working conditions in the sciences. Host Tony Van Witsen opened the discussion with some revealing numbers about today’s scientific workforce. A survey by the National Postdoctoral Association showed 86.6%of postdocs who responded were worried about job security. 87.4%were impacted by lack of clarity about their time as a postdoc. 94.5% said they were impacted by lack of clarity about their next position. Almost 95% said their professional and personal lives were most negatively impacted by their salary.

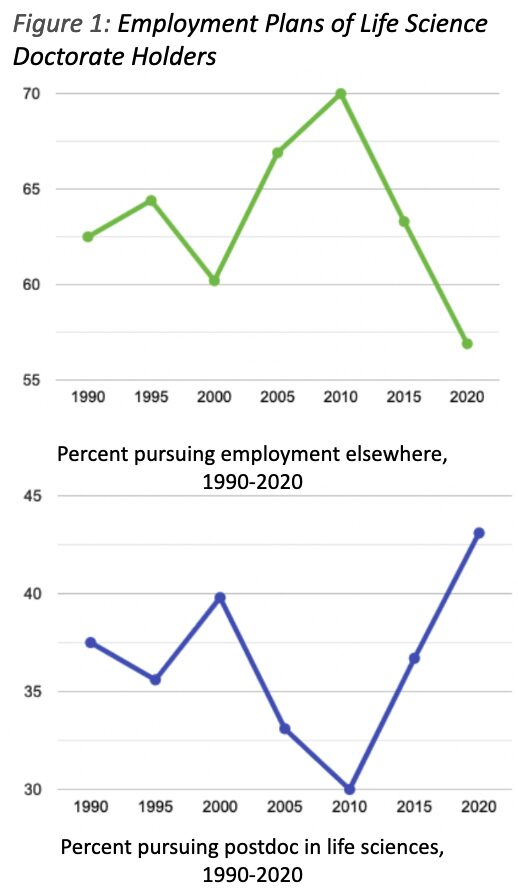

Consistent with those views, figures from the National Science Foundation’s annual survey of earned doctorates show a decreasing number of life science doctorate holders planning to pursue postdoctoral training and an increasing number leaving academia to pursue employment elsewhere. The lines made by the graphs of these two trends are almost perfect mirror images (Figure 1). In 2022, the percent leaving reached 53%, meaning it was literally off the chart. Anecdotal reports also indicate that many lab heads, the principal investigators (PIs), struggle to find enough qualified postdocs to fill the jobs they have at the salaries they can afford to pay.

What is driving this wave of discontent? ”The key thing,” said panelist John Walsh, a science policy scholar at Georgia Tech, “is the changing organization of academic scientific work. Science is increasingly organized around larger and larger research teams. Those generate a growing need for supporting members on the team.” In Walsh’s view, the hierarchy is built into the way contemporary scientific research is organized. “If you’re in this structure, we can’t all be head of a ten-person lab.”

When Walsh examined thousands of scientific papers over a period of decades, he found a pattern of increasing dominance of science by a smaller number of lead authors and a larger and larger number of supporting team members. A kind of emerging scientific class structure. Over the years, Walsh found an increasing number of scientists, mostly the supporting team members, were exiting the field. Lead authors gradually acquired significantly higher production and collaboration rates than supporting authors, who, over time, worked on fewer papers with fewer collaborators.

Complementing that global view, panelist Esra Yalcin talked about the challenges of daily life for postdoctoral scholars. Yalcin, a neuroscientist, is president of the Boston Postdoctoral Association, as well as a former postdoctoral research fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital. “I am coming from the very bottom of this hierarchy,” she said, adding personal testimony to the statistics about low pay. “Imagine that you’re 30 years of age. You’re about to start a family, but after holding a PhD degree, you’re still earning slightly above the low-income rate where you’re living. We found 20% of postdocs are parents. Childcare consumes one parent’s salary in Boston. Add other consumables, formula, other stuff the baby would need, it became impossible. It was evident that postdoc parents need some additional support.”

Panelist Holden Thorp, who currently serves as editor-in-chief of Science magazine, also spent a decade as chancellor of the University of North Carolina and was provost of Washington University in St. Louis as well. As a seasoned academic administrator, he believes the current problems afflicting the scientific workforce are symptoms of deeper institutional dysfunction. “The administration and the really powerful PIs don't want to deal with this,” he said. “Nobody wants to say, ‘Hey, we, we take advantage of all these people in order to get these wonderful discoveries that we're constantly bragging about.’ The solution is for administrators to pay attention. But if they do, their board's going to say, ‘Why are you doing that?’ Boards don’t do anything hard until they have to.”

The difficult career problems of young scientists land on the desk of Daniel Olson Bang, who has spent a decade at Syracuse University helping graduate students and postdoctoral scholars find ways to overcome these professional challenges. He says scientists in training often spend such long hours focused on their work that they wind up socially isolated, unable to see other career paths. “They know their PI, the lab mates, and that's it,” he says. “Many people, especially when you've gotten to the postdoc period, have spent so much time in what I would call an academic normative language that speaks about an academic, tenure track position as what you'll do. People far along in their programs don't really have a vocabulary or awareness of what else they might do.“

Thorp and Yalcin both recognized the relative powerlessness of the early career researcher and strongly criticized scientific institutions that preside over present working arrangements. Apologizing for her bluntness, Yalcin said, “This way of postdoc salaries coming from the PI's grant is, unfortunately, an opportunity to abuse the postdoc because it's uncontrolled money. The money goes into a gray zone where the institution doesn't owe you because the institution doesn't pay your salary. NIH doesn't have a system to protect the well-being of the postdocs.”

“As Dr. Yalcin said,” Thorp added, “The institution can't implement the fine ideas that John Walsh had, because it doesn't address where the power lies in the institution.” Thorp believes the growth of organizations like Yalcin’s, the Boston Postdoctoral Association, are symptoms of a deeper problem. “Higher education is under enormous strain,” he said. “The first question would be, how you're going to make life better for the students, staff and faculty. I think it's going to be hard, but there's a chance that that could happen, given all of the noise that's out there. Something has to give.”

“There are difficulties figuring out what to do if you don't end up as the hotshot PI, but want to continue and do the research that you've signed up for.” Olson Bang added. “That's a very hard topic to talk about. Is there a viable other tier? Are there research institutes where you can do the things you signed up for?”

The most visible evidence of early career scientist discontent has been the wave of union organizing and strikes taking place at campuses across the country. Most members, as well as those doing the organizing, have been graduate students and postdocs, a group not traditionally known for their political engagement. In that sense, the rise of labor organizing represents something completely unprecedented in American science. The trend has accelerated in the last two years, and encompassed some of the highest-profile, most prestigious institutions. AtUniversity of California, 48,000 postdocs, teaching assistants and researchers went on strike at ten campuses and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory last year. Other unions have targeted MIT, Cornell, Northeastern, Yale, the University of Chicago, Stanford, NYU, the National Institutes of Health as well as Weill Cornell Medical College and Mount Sinai School of medicine in New York. Most of these organizing efforts have happened since 2022, suggesting that this wave of unionization isn’t over.

Much of this organizing is focused around economic issues, particularly salary, but power imbalances between workers and supervisors are also important. A survey by the Caltech Grad Researchers and Postdocs union found more than 46% had experienced or witnessed bullying behavior, sexual harassment or discrimination of some kind. “When there is misconduct in a lab setting, your first channel supposedly is within the institution,” Yalcin said. “But obviously the institution is in a conflict of interest with themselves and with the PI.”

“Nothing made me angrier, when I was a provost,” Thorp said, “than for a graduate student to come to me and say, ‘I want to go to industry, and I told my PI this, and now he won't talk to me.’ I wish I could say that doesn't happen, but it does. And the administration cannot disabuse people of it. They don't have the leverage to do it anyway, because a lot of these folks are bringing big grants in and making the institution look good.”

Yalcin explicitly chose to help organize the Boston Postdoctoral Association rather than a traditional labor union. She felt that approach promised a better, more immediate answer to the problems of Boston area researchers even though she’s pro-union in principle. “I think a lot of it tracks with what’s gone on in the broader career world post-pandemic,” Olson Bang says of the organizing efforts. “There's a belief among postdocs and others that they should be able to get part of that too. The fact that there is already an unfair structure that doesn't pay them a living wage just adds fuel to the fire.”

Walsh believes science must abandon the idea that everyone needs to aim at becoming a principal investigator—hotshot or not—and instead, embrace the emerging two-tiered workforce structure. “We need to do more to support supporting scientists as a legitimate career path,” he says. “We need to rethink the careers and the job stability of this kind of scientific work, create career ladders similar to the tenure track faculty. We need to increase the legitimacy of this.”

View the full event recording on ESAL's YouTube channel.