Kate Burns serves as the director of state and local innovation at the Federation of American Scientists, building on her prior role as Executive Director at MetroLab, where she helped translate research into real-world policy initiatives. MetroLab operates on a two-fold mission: to embed science in cities, and to build transformative partnerships between public agencies and universities. Now an integral part of the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), MetroLab supports civic innovation and brings added capacity to cities and counties. Burns’ impactful work involves making this mission a reality. She bridges the gap between research, public policy, and local governing - making research accessible through data-driven civic efforts.

JL: Can you share what initially drew you to work at the intersection of policy and local government?

Burns: I studied journalism at the University of Kansas but actually started my career at an engineering firm, where I became fascinated by municipal infrastructure. That curiosity led me to government affairs within the firm and eventually to law school with the goal of working in local government. I interned for Mayor Sly James in Kansas City, Missouri, and was later hired to focus on innovation policy—drafting ordinances for rideshare platforms like Uber and Lyft and short-term rentals like Airbnb. Mayor James encouraged creative legal thinking, which helped deepen interest in policy governance. That path ultimately led me to MetroLab, where I’ve been able to comfortably sit at the intersection of innovation, research, and local government.

JL: In your current role, what local policy initiatives have you been most proud of—especially those you feel have had the greatest impact?

Burns: One initiative I’m especially proud of is MetroLab’s Data Governance Guide, which we published last year. I love this work because data is really the foundation of so many local government projects. It drives decision-making and policy and is the bedrock of any successful local campaign. The guide provides practical tools and policy templates to help cities manage data responsibly across its lifecycle. It helps cities strike a critical balance: ensuring transparency so residents understand what’s happening in their government while also protecting personal privacy where appropriate.

From MetroLab’s perspective, it’s about putting strong data principles in place. I also think our broader view of innovation in government is evolving in a really encouraging way. Initially, innovation meant using new tech: think sensors, smart infrastructure, things like that. But COVID forced cities to rethink that, to ask how government can truly meet residents’ needs, now and in the future, using novel concepts. To me, innovation today is about embedding that mindset across departments—applying it to housing, climate resilience, and safety-net programs for people living paycheck to paycheck.

JL: How does data play an active role in evaluating the needs of the public?

Burns: Technology and data analytics play a crucial role in helping local governments deliver services like trash collection, street maintenance or building public infrastructure. With limited budgets, cities and counties need to be efficient while also being effective, and that starts with using data to guide decisions and investments.

There are two kinds of data use: one that informs and one that influences behavior. A great example is highway traffic signs—seeing “20 minutes to your exit” informs you but doesn’t change your actions. You have to sit in the traffic. But a crosswalk countdown clock? That’s actionable data—it helps you decide whether it’s safe to cross or wait.

Today, we’re working on a national project asking local governments what kind of research they need most – and over and over, they tell us they want better tools to evaluate whether their interventions are working. Cities are eager to measure impact more thoughtfully, and data are at the heart of that effort.

JL: How do you see the future of STEM policy shaping communities and social development?

Burns: I think the future of STEM policy lies in making research truly equitable and accessible—not just available to those with institutional access or academic credentials. That means eliminating paywalls, involving communities from the beginning, and ensuring that people understand the outcomes of the research they’re part of. At MetroLab, we focused on bringing research out of peer-reviewed journals and into city halls where it can inform real decisions. To do that effectively, research needs to align with the day-to-day processes of local governments. If you're working with a city to introduce a new technology or policy idea, you need to understand how procurement works, how ordinances are changed, and what regulatory mechanisms are in place. If you're advocating for innovation in permitting, housing, or mobility, you need to meet local governments where they are, within the systems and timelines they already have in place.

Beyond that, some of the most meaningful change happens when research supports areas outside a city’s formal control, like school systems. In these cases, mayors and civic leaders can still champion change by amplifying community voices and using research to support grassroots movements. But accessibility matters just as much as advocacy. We need research presented in plain language, ideally at a seventh-grade reading level or below, with public summaries, appendices, and visual data that anyone can understand. And it should be easy to find—freely available and searchable.

JL: Have you ever observed a disconnect between what your organization focuses on versus what the public wants?

Burns: I’ve definitely seen disconnects between policy initiatives and public sentiment. One clear example was during my time working on laws around short-term rentals like Airbnb in Kansas City. The city was dealing with a lot of blight, and we saw short-term rentals as an opportunity to revitalize vacant or underused properties. There was potential for economic benefit. But despite the policy's promise, there was resistance to change. So the process of developing the ordinance took years and required a long, careful public comment process to strike a balance between novel policy and neighborhood concerns. It taught me the importance of engaging early and often, and recognizing that even well-intentioned policy can face pushback when the public doesn't feel heard.

Another example is from a long-running resident satisfaction survey the city conducted. For nearly two decades, residents consistently said their biggest frustration was potholes and deteriorating infrastructure. The problem was that the city didn’t have the budget to address it. Eventually, we used that survey data to craft a clear message: “You’ve told us what you want—now help us fund it.” That messaging supported the successful passage of a $700 million General Obligation Bond, approved by nearly two-thirds of voters. That moment underscored the power of listening and translating public feedback into actionable investment. But it also highlighted a key challenge: cities often lack the resources to consistently communicate with residents. Policymakers have a responsibility to bridge that gap. If a policy is truly for the public good, we need to be able to tell that story in a way people understand and support.

JL: What’s one of the biggest changes you’ve witnessed when research is brought closer to the people it’s meant to serve?

Burns: One powerful shift I’ve seen is researchers getting off campus and engaging directly in city halls or alongside residents instead of just publishing white papers. That kind of hands-on collaboration is where real impact is seen. For example, the University of Miami created a dashboard that overlays housing cost burden with climate risk. In Miami, a large percentage of residents spend over half their income on rent, and the region is also at high risk for sea-level rise. The dashboard helps the city visualize where those overlapping vulnerabilities exist and plan accordingly.

Another great example is a National Science Foundation Civic Innovation Challenge project in New York, which set up a network of hyper-local flood sensors in low-income neighborhoods. When flooding occurs, the sensors trigger automatic payouts from a third-party insurance provider. This bypasses the usual claims process and delivers immediate relief. That’s a game changer for families living paycheck to paycheck. These kinds of projects show the power of community-embedded research. With initiatives like the CHIPS and Science Act and the NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines program, we're seeing more investment in building authentic, effective partnerships that bring real solutions to the table.

JL: Could you share more about your ongoing partnerships and how they facilitate successful engagement?

Burns: In many ways, MetroLab’s work with the National Science Foundation’s Civic Innovation Challenge captures the heart of our mission. As a grantee and technical assistance provider in the program, MetroLab plays a unique role by supporting dozens of community initiatives. We help build a community of practice by guiding teams through deployment, community engagement, and the challenge of making projects sustainable, scalable, and transferable after federal funding ends.

The Civic Innovation Challenge delivers rapid, local impact by investing $1 million over 12 months to test ideas developed in partnership with the people they’re meant to serve. This can include guiding pilot teams or supporting early-stage grantees in imagining what change could look like in their neighborhoods.

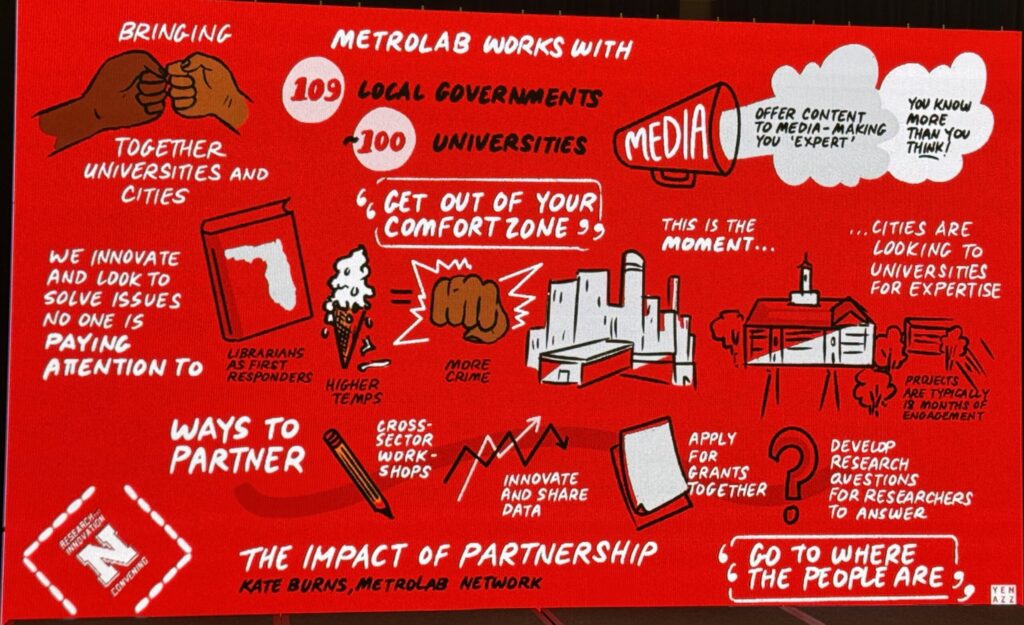

To date, MetroLab has worked with over 90 local governments and 120 universities. While we began by fostering partnerships around technology, our mission has since expanded to focus more broadly on how research can proactively deliver innovation. To help realize this vision, MetroLab’s next chapter is joining the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). FAS is a nonprofit organization working to drive progress on the most pressing issues of our time by ensuring science, technology, and evidence-based policy have a seat at the table. Together, MetroLab and FAS are strengthening the bridge between research and action.

Are you involved with an organization or effort that you think might be of interest to the ESAL community? Or have heard about an organization or initiative that you’d like to learn more about? Let us know here, and we may feature it in a future post.