Communication, Politics, and Science at AGU 2019

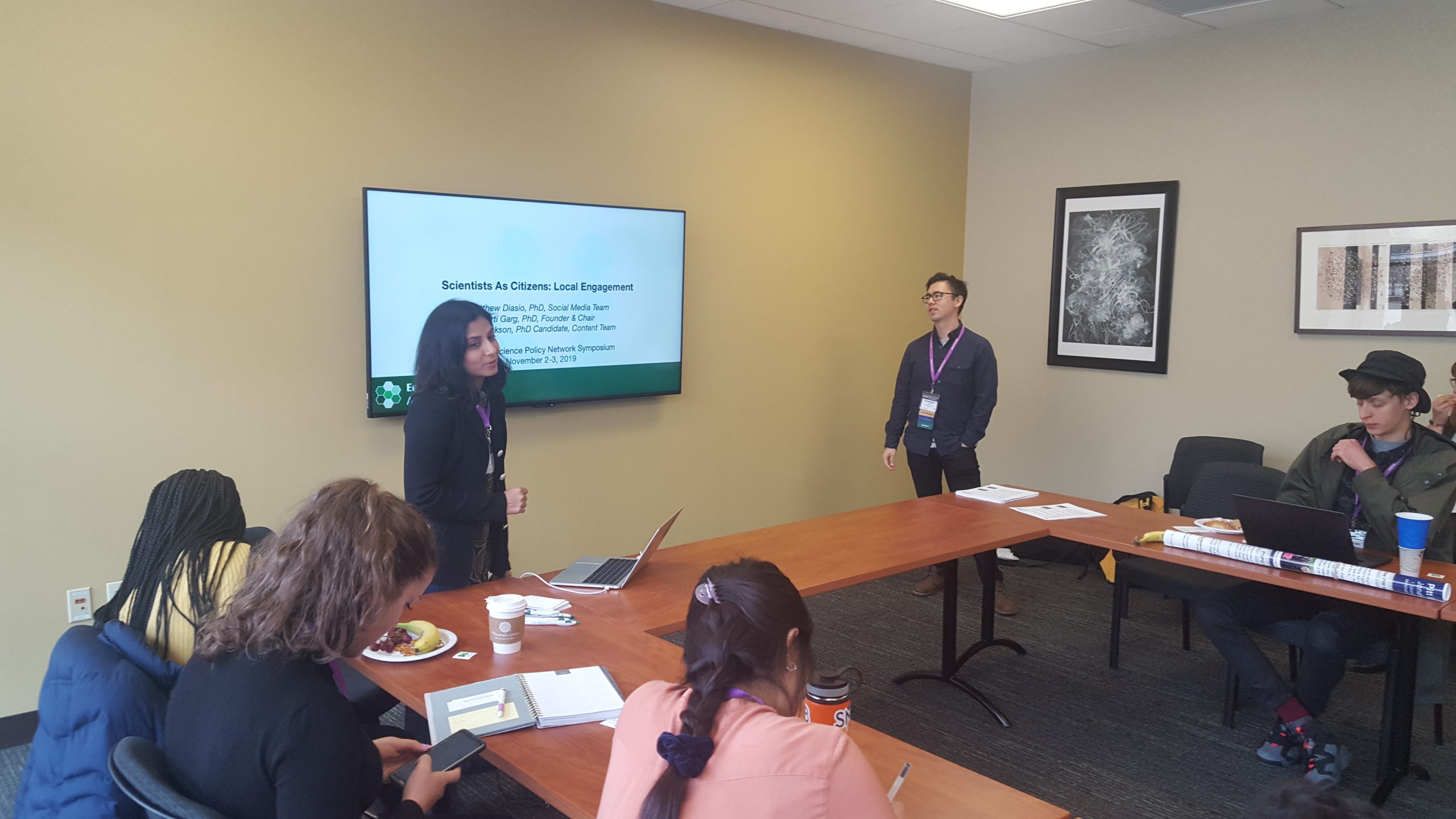

At this year’s American Geophysical Union’s 2019 Fall Meeting, Engineers & Scientists Acting Locally (ESAL) hosted two sessions about scientists engaging as citizens in their communities. They brought together diverse groups of scientists who shared experience, advice, and inspiration about impacting city, regional, and state policies.

Over the two sessions, panelists and presenters talked about the rewards, as well as the challenges, of community and local government engagement. A common refrain from all commenters, many of whom also had federal policy experience, was the ability to make a larger and more immediate impact at the local level. To effect these changes, developing and leveraging communication skills, especially the ability to respectfully listen to input from diverse and unfamiliar perspectives, emerged as critical to local engagement.

Peter Fiske, director of the Water-Energy Resilience Research Institute at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, kicked off a session of oral presentations by offering an unusual take on communication. Fiske discussed how civic engagement could help us further develop as scientists by teaching us to be empathetic communicators who can make information accessible to our audience. As scientists, this audience may include our funders and our students...groups of people who will be most receptive to our ideas if we can relate them to familiar concepts.

Discussions during an ESAL-organized town hall also emphasized the need for empathy as part of impactful policy discourse. Julianne McCall, a science officer for the California Governor’s Office of Planning, related how listening to constituents can guide effective policy implementation. McCall recounted how speaking to Californians in low-income, rural communities provides insight into the day-to-day hurdles that prevent them from seeking preventive care, even though it lowers costs and improves health outcomes. These kinds of discussions inform programs where community assets, such as churches or schools, become temporary clinics for delivering preventive services.

From left to right: Aimee Bailey, Kendra Zamzow, Julianne McCall, and Ginny Delaney. (Photo credit: Melissa Varga).

Kendra Zamzow, staff scientist at the Center for Science in Public Participation, provided practical advice on how scientists should present themselves depending on their context. Zamzow includes “PhD” in her signature in order to establish her expertise when providing input to policymakers on regulatory issues. When talking to communities who may be impacted by regulatory decisions, however, she does not lead with her scientific credentials so that they feel more comfortable sharing their perspectives and experiences. By being mindful of how her audience perceives her, Zamzow can more effectively communicate with a variety of groups.

Speakers and panelists also discussed the need for honesty when communicating with the public, even when it can be uncomfortable. During his presentation, Jeffrey Warren, research director for the University of North Carolina Research Collaboratory, spoke candidly about how his political affiliation with the Republican party helped him become science and energy advisor to the North Carolina General Assembly after Republicans took control of both chambers in 2010. While he acknowledged that today’s Republican party is often seen as anti-science, he said that many policies were more evidence-driven because he was in a position to inject science into deliberations. He also reminded attendees that scientific evidence is only one of several inputs a policymaker considers, and building trust can help make them take your input seriously.

Zamzow and Ginny Delaney, a program officer for the University of California Office of the President and a municipal task force member, both shared stories where following the science resulted in their taking policy stances at odds with the communities with which they typically aligned. For Zamzow, this involved an aspect of upgrading water quality standards in Alaska and for Delaney it involved the siting of a marijuana dispensary. While taking evidence-backed stances that counter popular opinion in your community can be uncomfortable, their experiences underscore the perspective scientists can bring to policy discussions. While all of the speakers acknowledged that the path to making policy impact traversed difficult and sometimes unnavigable terrain, they all encouraged attendees to take their first steps to what they have found to be rewarding destinations and stops along the way.

Thursday’s session was a town hall entitled “Shaping Science-Informed Policy at the City, County, and State Levels”. Panelists included Aimee Bailey, Director of Decarbonization and Grid Innovation at Silicon Valley Clean Energy, Delaney, McCall, and Zamzow. The discussion was moderated by Arti Garg, Founder & Chair of ESAL. Friday was an oral session and panel entitled “Science to Action: Scientists as Citizens Contributing Skills to Policy Making I”. Presenters included Fiske, Warren, Samantha Lichtin, Legislative Liaison & Policy Analyst for the Colorado Energy Office, and Shaughnessy Naughton, Founder of 314 Action. The oral presentation was followed by a panel discussion moderated by Melissa Varga, Community Manager and Partnerships Coordinator at the Union of Concerned Scientists, and Zamzow..